Making a Case for Environmental Flow Standards

The rivers that flow through our communities, cities, and countryside have historically shared an important mission: arriving at the coast. But what if rivers aren’t able to reach their destination? Pressure on water resources can cause this to happen, and when it does, estuaries cease to function, economies suffer, and coastal wildlife is diminished.

Take the Colorado River, for example. From its source high in the Rocky Mountains, the expansive river carries its water south for nearly 1,500 miles, through deserts, the Grand Canyon, across Lake Mead, and finally, to the Gulf of California and the Pacific Ocean.

The Colorado River in California.

But today, the Colorado River doesn’t reach its destination, instead drying up in the deserts of Baja California and Mexico. Once the home of a highly productive habitat, the remains of the river are now a barren wasteland.

The example of the Colorado River raises an important question: How can water managers and policymakers improve such struggling ecosystems, while still providing water for human needs? The answer starts with understanding how much water a river truly needs to reach its final destination and sustain its aquatic ecosystem.

How Much Water Does a River Need?

The science of environmental flows is used to determine the amount of water that should remain in a stream or river for the benefit of the environment of the river and its downstream estuary. Water flows express the quantity, quality, and timing of water that are necessary to sustain a river and its associated fish and wildlife. Each river has its own unique patterns that align with nature’s cycles to support flourishing ecosystems, all the way from the river’s source to its terminus.

Texas river channel water flow.

The importance of a river’s flow regime for sustaining biodiversity and ecological integrity is well established. If too much water is taken from a river, the river’s natural flow will be altered dramatically. In order to reduce future ecological damage, the water needs of river ecosystems must be proactively addressed.

“First in Time Is First in Right”: Water Rights Affecting Environmental Flows

Most western states operate primarily on the prior appropriation system, in which the oldest water rights have the first available claim on the available water, that is, “first in time is first in right.” However, during droughts, water may not be available for all. Senior water rights holders may receive their full permitted amount, but junior water rights holders may not. In this scenario, in the absence of environmental flow requirements, the river itself may go dry.

A California river dried up.

As water demands increase, the impacts on the rivers will be especially severe. The challenge is this: setting environmental flow standards necessary to provide sufficient flow for wildlife and habitat comes at a potentially steep expense for people and businesses, in particular, the agriculture industry. The challenge is to build community support for this expense, and to do that consensus must be reached on how much water the river needs and the value of that amount. Then the community can progress towards an equitable distribution of water between human needs and the environment.

Environmental Flows in Texas: Applying Standards Across a Variety of Systems

The state of Texas offers an example of how environmental flow standards can help balance the needs of people with the well-being of vulnerable riverine ecosystems. Prior to 1985, environmental flow conditions were rarely imposed on Texas water rights. Then, in 2007, the Texas legislature created a program to identify environmental flow standards statewide. The process of determining these environmental flow needs should be viewed as an iterative process, in which each water management action such as flow restoration must be monitored and evaluated carefully.

South Texas River.

While it may be a challenge to identify environmental flow needs across large river basins, one innovative method for achieving this is to look at historical hydrology, because that historical hydrology is what created the ecosystem. The Hydrology-Based Environmental Flow Regime (HEFR) method, which was developed and is applied in Texas, combines a suite of user-customizable hydrologic statistics with an implementation framework. The HEFR method is particularly effective because its calculations have enough flexibility to adapt to a wide variety of riverine systems and its outputs are suitable for incorporation into water rights permits. This allows science and policy to be uniquely coordinated.

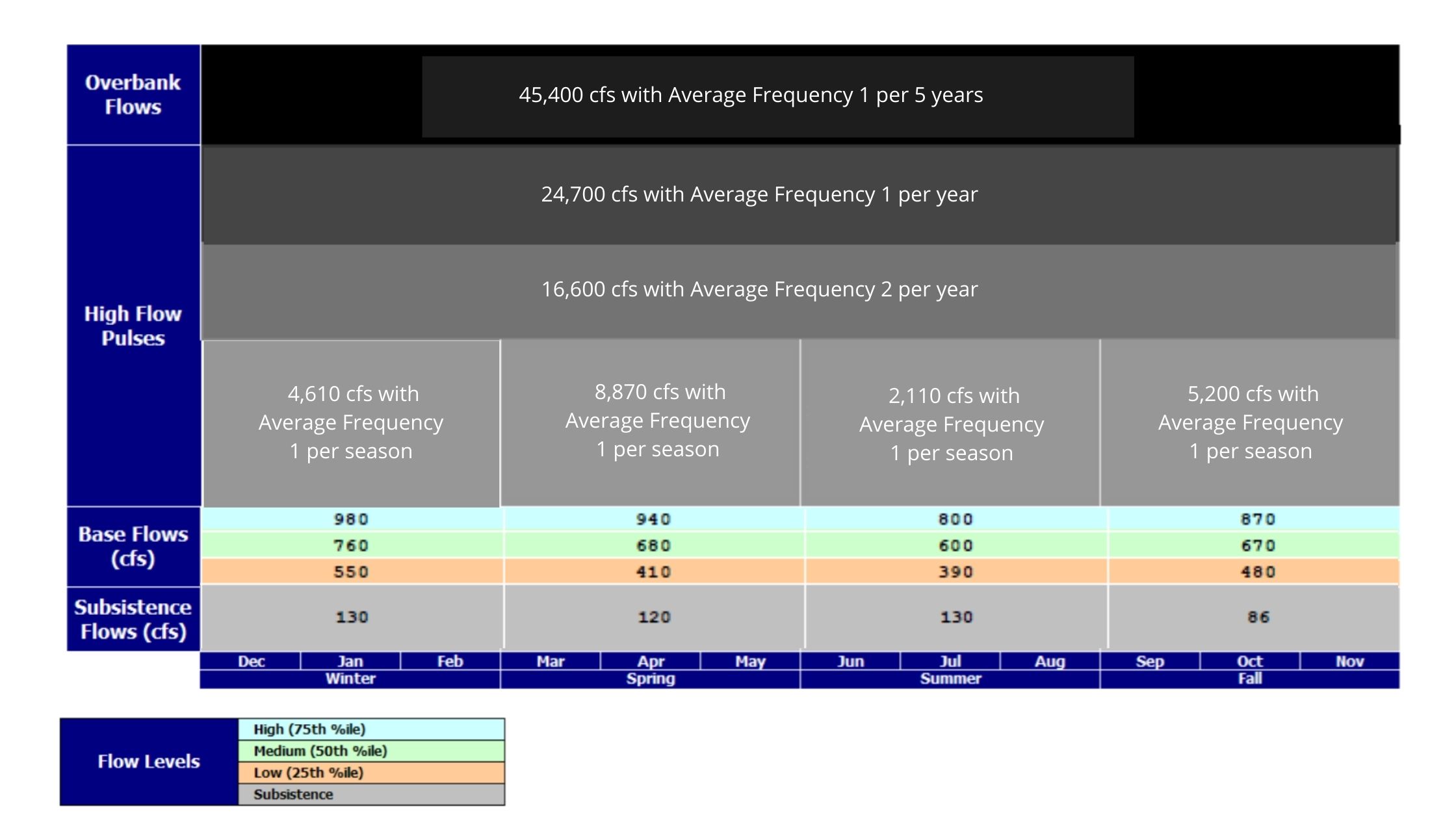

Flow statistics, such as those calculated from a historical record by HEFR, quantify a subset of the natural range of flows experienced in a river. Listed below are the flow categories, each of which are quantified across different seasons and different hydrologic conditions (e.g., dry or wet periods):

- Subsistence Flow: the minimum streamflow needed during critical drought periods

- Base Flow: the “normal” flow conditions found in a river, in between storms

- High-Flow Pulses: Short-duration, high flows within the stream channel that occur during or immediately following a storm event

- Overbank Flow: infrequent, high-flow events that exceed riverbanks

Example of a brief Environmental Flow Regime Recommendation. Episodic events are terminated when additional volume or duration criteria are met.

Collectively, this subset of flows provides much of the ecosystem functions of the natural river, such as sediment transport, habitat for fish connectivity, and fostering riparian vegetation. Together, flow guidelines, along with implementation rules, comprise environmental flow standards intended to limit the effects of water withdrawals on instream flows and flow-dependent ecosystems. Ultimately, altering the natural flow pattern takes a serious toll on the ecological habitats that depend on it. Setting environmental flow standards can shape the quantity and timing of flows that are available for humans to alter or divert, resulting in less harm to aquatic ecosystems.