3 Recommendations for Offshore Wind Planning in the U.S.

In 2001, the first ever offshore wind farm in the United States, off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, was proposed and on track for a successful launch. However, after 16 years of planning and design, the Cape Wind project was ultimately terminated, in part due to litigation setbacks and concerns from the local community.

Offshore wind is poised to become a linchpin in the renewable energy expansion; planning for this energy source has been rapidly growing since the Biden-Harris Administration announced the goal of producing 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind energy by 2030. While data abounds regarding the technical aspects of offshore wind energy, there is little relative information or knowledge about how the nearby communities feel about offshore wind, especially over time. The demise of Cape Wind is an important lesson in how the success of such projects will likely depend as much on whether developers, regulators, and agencies prioritize social perceptions and community relationships as they do on technological innovation, engineering, design, and financing.

Offshore wind energy is expanding rapidly in the United States, as the Biden Administration has set a target of 30 GW of power production by 2030 via offshore wind.

What Influences Attitudes toward Renewable Energy?

Understanding how local attitudes toward commercial-scale renewable energy change over time should provide insights into how to engage communities and influence public acceptance. Attitudes towards offshore wind are influenced by a variety of factors, including aesthetics, environmental impacts, and procedural justice or governance.

Additionally, it is important to take the long view of what influences attitudes because offshore wind farms take years to plan, develop, and build. In other words, if individuals who are initially supportive develop negative perceptions over time, or vice versa, we need to know what factors drive their attitudes. With this understanding, community concerns may be better understood, acknowledged, and remedied in good faith so that offshore wind projects have a better chance of success.

Learning from the First Operational Offshore Wind Project in the U.S.

In 2016, the Block Island Offshore Wind Farm (BIOWP)—3.8 miles from Block Island, Rhode Island, and 18 miles from the mainland—became the first commercial offshore wind farm in the United States. Its five turbines transmit 30 megawatts (MW) of power to the electric grid along a 21-mile transmission submarine power cable buried under the ocean floor. Before the wind farm became operational, Block Island’s isolation from the electric grid made it difficult to meet its unique energy needs. The entire island relied on only five diesel generators to power the homes of 1,000 year-round residents, businesses, and up to 20,000 summer tourists.

The Block Island Offshore Wind Farm is visible from certain points on the Island and the mainland.

To observe how opinions towards the BIOWP fared over time, Dr. Jeremy Firestone, Dr. David Bidwell, and I analyzed panel data from a survey of Block Island residents and mainlanders (coastal Rhode Island residents who may be affected by the view, planning process, or general construction impacts) from 2016-2018, the months before turbines and one-year post-operation for a look into life before and after the BIOWP. Our sample was comprised of over 390 residents who responded to both surveys in 2016 and 2018, answering questions based on their supportive, opposed, or undecided opinion about the BIOWP, as well as turbine aesthetics, the planning process, and the environmental impacts of the project. Some questions gauged more internal variables, such as people’s confidence in their views and how much they knew about the project.

We also followed up with phone or video interviews of 24 of the respondents in 2020 that expanded on the survey themes. The respondents were chosen based on their age, education, and subgroup to best contribute to the richness of the study. This mixed methods approach was valuable because it enabled us to analyze responses in people’s own words and supplement our quantitative survey results. That way, we could hear how someone felt about the planning process, not solely how they ranked its fairness on a scale of 1 to 5.

The electric cable buried in the ocean floor links Block Island to the mainland, giving the island access to power and high‑speed internet.

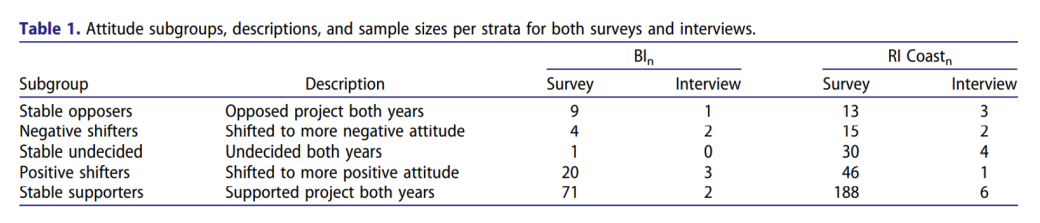

We sorted respondents into categories based on how their opinion about the BIOWP fared over time (our dependent variable). Three of the five groups comprised people whose opinions did not change: stable supporters, stable opposers, and stable undecideds. The other two groups were comprised of those people whose opinions fluctuated: positive shifters (people who grew to have a more positive view of the BIOWP by 2018) and negative shifters (people who developed more negative views of the BIOWP by 2018).

The dependent variable for the study is the attitude subgroup, including both survey and interview responses for Block Island and Rhode Island residents.

Based on a regression from our survey-based data, triangulation with our interviews, and statistical analysis, we found that certain characteristics animated each attitude subgroup:

Stable supporters displayed favorable impressions of aesthetics and supported the global and local benefits of the BIOWP. Global benefits included reduced carbon emissions, while local benefits included eliminating pollution and noise from diesel-powered generators, gaining high-speed internet access, and positive effects on fishing. Stable supporters were also very confident and knowledgeable about the project.

Stable opposers were largely affected by perceptions of unfairness regarding the developer’s and State’s communication and transparency throughout the planning process, by negative impacts to wildlife, and lack of information about those impacts. Additionally, this group perceived the wind turbines as having a negative impact on tourism and the “beautiful natural landscape.” Opposers were even more confident in their views and knowledgeable about the project than stable supporters.

Positive shifters credited their attitude change to the local benefits and improved perceptions of turbine look and fit with the landscape. They described a balancing act, as these positives outweighed the recognized drawbacks of issues with the planning process.

Negative shifters said that, while they support the environmental benefits of renewable energy, they distrusted the developer and felt “left behind” after the turbines were built. Another driver for negative shifters was the inconsistency of turbine fit with the beauty of the island and that the BIOWP’s appearance was much different than expected—almost as if the developers had “sold a good package to get through the permitting process.”

Undecided respondents were all mainlanders and tended to be either disengaged and uninformed about the BIOWP’s progress and impacts or still had unanswered questions about wind power’s impacts on wildlife, fishing, and the cost of electricity.

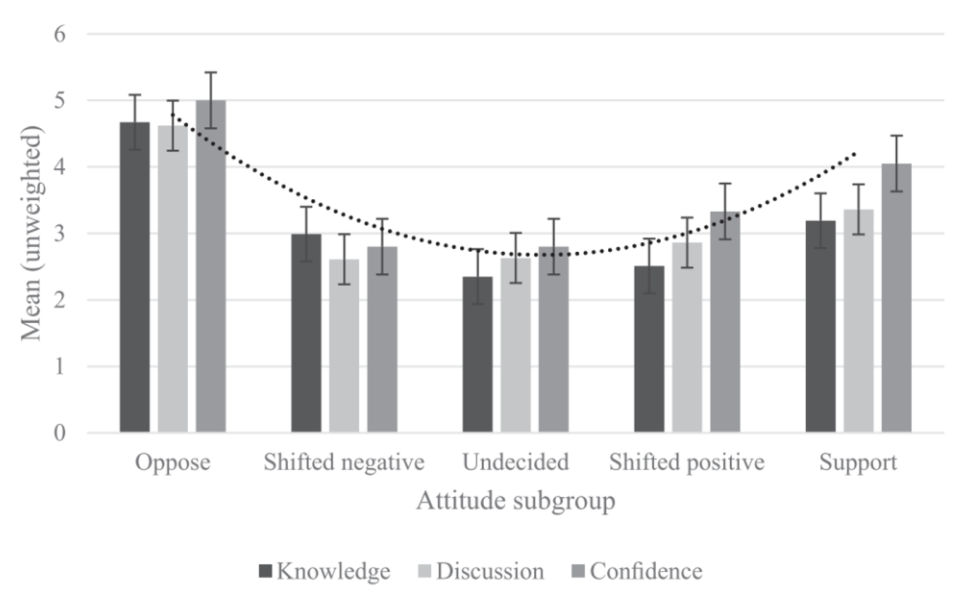

The undecided respondents and both attitude shift groups had much lower levels of confidence in their views and knowledge about the BIOWP and reported less frequent discussions about the BIOWP with family and friends.

These results illustrate the level of discussion, knowledge, and confidence in views across each subgroup, with the dotted trendline tracing a convex pattern across means for subgroups.

3 Recommendations for Offshore Wind Developers and Coastal Communities

Using these multilayered results, we developed recommendations for offshore wind developers and communities to better foster community relations from planning to operation.

- Demonstrate the Reality of Turbine Aesthetics: Attitudes can be significantly influenced by differences between expectations and reality of turbine aesthetics. Therefore, developers should aim to be as transparent to the community as possible, using realistic photography and simulations. Community leaders can recommend that residents visit similar projects to gain more realistic perceptions of how wind turbines appear from shore; this is a more actionable suggestion along the East Coast, which offers greater access to similar sites than elsewhere.

- Facilitate Information Sharing: People that were more knowledgeable about the BIOWP were surer about their opinions and less likely to shift viewpoints. Planning regular communication is essential, even into the operational phase, because many negative shifters felt “left behind.” Communication tools should be geared for the targeted audience (e.g., social media for younger audiences and newspaper articles for older audiences). We also encourage stakeholders to view environmental impact statements as more than a regulatory requirement but rather as a tool to share science-based knowledge about project designs and effects.

- Gain Long-Term Trust in a Community: Communication and information are key, but they are more valuable when they come from trusted sources. Opposers and negative shifters were strongly influenced by feelings of broken trust or feeling left behind by developers. We recommend developers hold community sessions before, during, and after a project is built. Following up with communities into the operational phase—for example, through focus groups and community sessions about project updates—may be useful in building, maintaining, or even salvaging trust. Having a community liaison, as in the case of the BIOWP, may also prove beneficial.

Ultimately, while scientists, engineers, and developers must collaborate from a technical standpoint, an equal emphasis must be placed on social responses to planned offshore wind developments. With most offshore wind projects in the United States in the planning stages, it will prove critical to continue to invest in collecting and analyzing longitudinal social science data on coastal residents attitudes toward renewable energy projects.

Explore the entire analysis of the Block Island Offshore Wind Project in Rhode Island in the Journal of Environmental Policy and Planning, “Winds of change: examining attitude shifts regarding an offshore wind project.”